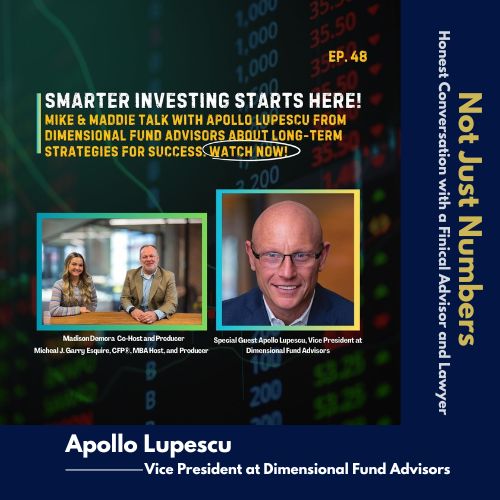

Episode 48: Investing Smarter: Strategies for Long-Term Success with Apollo Lupescu

Hosts: Madison Demora and Mike Garry

Special Guests: Apollo Lupescu, Vice President at Dimensional Fund Advisors

Episode Overview

Listen to Our Podcast On:

TIMESTAMPS

00:08 – 02: 04 – Introduction of Apollo Lupescu from Dimensional Fund Advisors

02:05 – 06:31 – Who is Dimensional?

06:32 – 09:20 – Why Dimensional Puts Financial Advisors at the Center

09:21 – 15:32 – Mutual Funds vs. ETFs: Understanding the Differences and Choosing the Right Fit

15:33 – 26:46 – Demystifying Stocks: How Investing Builds Wealth Over Time

26:47 – 35:18 – Fixed Income: What Sets Dimensional’s Bond Funds Apart

35:19 – 46:20 -The Evolution of Investing: From Stock Picking to Asset Class Investing

46:21 – 52:34 – Global Investing: Why and How to Diversify Beyond U.S. Stocks

52:35 – 57:21 -Top 3 Investing Mistakes: Emotions, Concentration, and Lack of a Plan

Connect with our Special Guest

Follow Us on Social Media

Stay updated with the latest episodes and news by following us on social media: